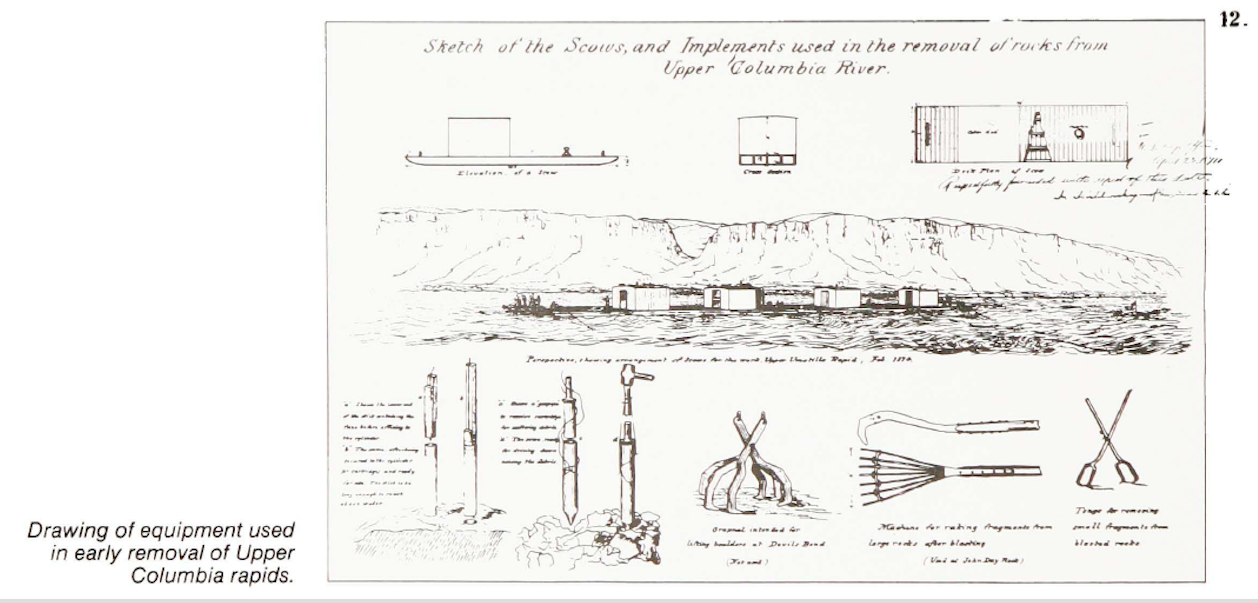

Figure 12 details both the US Army Corps of Engineers equipment used for removing riverine formations to "improve" channel navigability, as well as the Basaltic cliffs on Washington (for now) shoreline of the Columbia River-- Nch'i-Wána. Willingham, W. "Army Engineers and the Development of Oregon: A History of the Portland District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers." 1980, p13.

ROUTING THE SCENIC

In Routing the Scenic: settler colonialist sense and environmental culture in the Columbia River Gorge I examine the historical legacy and quotidian production of U.S. settler colonial violence through scientific practices.

The Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area is the largest national scenic area in the United States. Signed into federal law by President Reagan in 1986, the National Scenic Area Act (NSAA) marked a national first in bi-state governance and innovation in scenic preservation. Through the Act, Oregon and Washington formed a commission charged with land use planning and economic development along the Mid-Columbia River: Over 292,000 acres of rural, urban, and forest service land in the throes of recovery from extractive industry decline. Popular globally for its vistas and windsurfing, the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area is lauded as a turning point in “how the west is planned,” remade as an eco-playground through tourist and tech sectors despite decades of reconfiguration to accommodate hydropower and industry. Yet the Scenic Area preserved today is a product of 20th century settler nation-state formation characterized by dam construction, highway extension, and commercial fishing. In my research, I demonstrate how these projects of capital expansion relied on technologies of measurement, valuation, and boundary making that dispossessed and (re)spatialized the homelands and persisting political lives of Columbia River Treaty Tribes.

How can we understand the material and ideological consequences of environmental land use planning that emerges from, and is made possible by, the conditions of U.S. colonial dispossession and biologics that continue to produce housing shortages, barriers to economic self-determination, and violate federal Treaty? Scholars have theorized the historical co-constitution of power and labor through hydroelectric and fishery development in the Columbia River, and the role of Pacific Northwestern landscapes and scenery in shaping contemporary U.S. environmentalisms. However, what has remained unexamined is how scenic preservation—and the corresponding natural sciences and narratives that chart, measure, and demarcate scenery—is imbricated in the political and spatial ordering of Native lands. This project sheds light on historical relationships between the scientific technologies of making a “scenic river” and the (re)production of colonialist claims to land and cultural normalization of dispossession in the Mid-Columbia. I interrogate quotidian cultures of masculinist whiteness, cultures of ecological curation, and interlocking militarisms in Scenic space, with implications for contemporary anti-colonial environmental politics in a time of urgent climate change adaptation and global Indigenous social movements.

My future research builds on my work in the Mid-Columbia River to investigate toxic sediments and the diverse knowledge and management practices that converge and contest one another around various socioenvironmental harms that sediments produce. I propose that studying sedimentation can disrupt entangled violences and ecological changes that are often illegible or obscured in landscapes shaped by colonial territorialization.

How can we understand the material and ideological consequences of environmental land use planning that emerges from, and is made possible by, the conditions of U.S. colonial dispossession and biologics that continue to produce housing shortages, barriers to economic self-determination, and violate federal Treaty? Scholars have theorized the historical co-constitution of power and labor through hydroelectric and fishery development in the Columbia River, and the role of Pacific Northwestern landscapes and scenery in shaping contemporary U.S. environmentalisms. However, what has remained unexamined is how scenic preservation—and the corresponding natural sciences and narratives that chart, measure, and demarcate scenery—is imbricated in the political and spatial ordering of Native lands. This project sheds light on historical relationships between the scientific technologies of making a “scenic river” and the (re)production of colonialist claims to land and cultural normalization of dispossession in the Mid-Columbia. I interrogate quotidian cultures of masculinist whiteness, cultures of ecological curation, and interlocking militarisms in Scenic space, with implications for contemporary anti-colonial environmental politics in a time of urgent climate change adaptation and global Indigenous social movements.

My future research builds on my work in the Mid-Columbia River to investigate toxic sediments and the diverse knowledge and management practices that converge and contest one another around various socioenvironmental harms that sediments produce. I propose that studying sedimentation can disrupt entangled violences and ecological changes that are often illegible or obscured in landscapes shaped by colonial territorialization.